History Special 6: Crossing the Bridge

I. MADE OF WOOD AND PAPER Unlike Hinako Sugiura, Keiichi Hara is not an expert of the Edo period. Nevertheless, he was eager to offer the most accurate rendering of early XIX century Japan, as he did not want to disappoint Sugiura if she could see the film. However, a major challenge to the production staff was posed by the fact that Tokyo had been destroyed twice since the age of Hokusai and O-Ei. What survived was replaced with more modern buildings, in a process that changed the cityscape dramatically. Unlike most European cities, where two-century-old buildings are not uncommon, Edo was literally made of wood and paper, and virtually nothing of that world can be seen in present-day Tokyo.

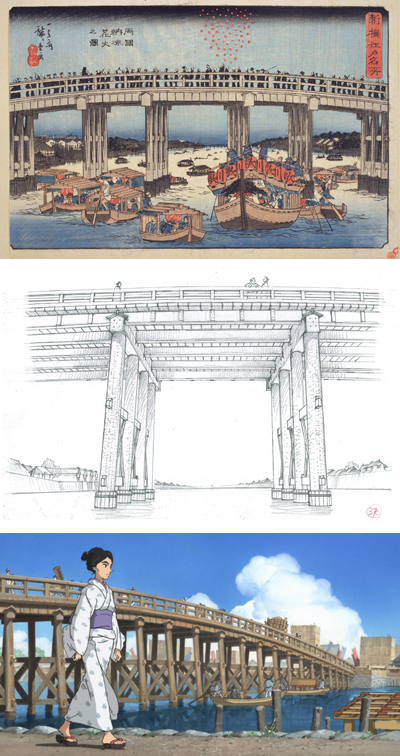

One of the city landmarks of the time was Ryogoku Bridge, which is also an iconic element in Miss Hokusai, making its first appearance at the very beginning of the film. Hara put much importance into this artifact, as people of any walk of life incessantly crossed this bridge on the Sumida River. It was the heart of the lower city of the commoners, and connected Honjo on the east bank, where Hokusai lived, with Asakusa (a major temple and market square), Yoshiwara (the pleasure district) and the great kabuki theatres, all located on the west bank. The surrounding area at both ends of the bridge and along the river bustled with any sort of trade and entertainment activities, with dozens of street peddlers, food stalls, tea houses, attraction shows, and the Ekoin Temple, used as arena for sumo wrestling matches.

As Sugiura once explained, bridges also connect the real world on this side of the river, with the ideal (if not even the "other") world on the opposite one. The bridge itself was a place suspended in between these two realities, a symbol of the transient nature of the "floating world."

II. A BRIDGE TOO FAR The bridge has a dramatic history. As the Sumida River defined a province boundary, it was deemed a natural defense to the city of Edo, therefore the security-obsessed Tokugawa administration had prohibited the construction of bridges across the river, other than the Senju Bridge, that Tokugawa Ieyasu had built in 1594 but much upstream and far from city centre. However, with the instauration of the Tokugawa government in 1603, Edo became the de facto administrative capital of the empire, and started growing exponentially, making it one of the most highly populated cities of the world. The area around the castle (today's imperial palace) was standing on a promontory called Yamanote, or mountain's hand, and was reserved to the residences of noblemen and local vassals' representatives. It was, literally, the Upper City. As the population increased and commoners needed to be settled, development of the east bank of the Sumida River started in earnest in the newly created villages of Honjo and Fukagawa (today's Sumida Ward and Koto Ward, respectively). The northern part of the west bank, known as Asakusa, also became part of this urban expansion. Along with Nihonbashi, these three districts formed the Lower City, or the area in Edo where commoners had permission to reside; but they were also deemed outskirts of the city, Honjo and Fukagawa in particular being considered far suburbs on the other side of the river.

Following the restriction against building new bridges, boats were used to ferry people and goods from one bank of the river to the other. However, in 1657 the Great Fire of Meireki ravaged the city of Edo for three whole days, claiming more than 100,000 victims out of an estimated population of 480,000 (approximately 30,000 victims on a population of 280,000 per other estimations). The dramatically high number of causalities was in part to be attributed to the fact that many people remained trapped between the flames and the waters of the Sumida River on the west bank. The extensive destruction brought by the fire urged a large-scale urban reorganization of the entire city, and permission was given to build a second, larger wooden bridge, 200 meters long and 8 meters wide, that was completed in 1659. Initially called Great Bridge, it was later renamed Ryogoku Bridge, and greately contributed to the further urban development of Honjo, that was to become one of the most densely populated area of the city. Here Hokusai was born in 1760, and here he lived for almost his entire life. Three more bridges were going to be built in the following years.

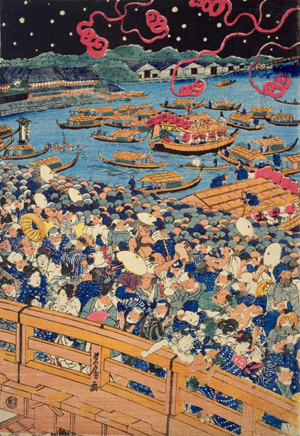

III. RYOGOKU 1814-2014 A bridge called Ryogoku can still be seen in Tokyo today. It stands about 20 meters downstream from its ancestor's original location, and it is made of concrete and steel. The only way to know how it looked like two centuries ago, is to refer to the photographs of the time: ukiyo-e. Luckily, and unsurprisingly, the bridge was a favourite subject, one of those "famous places of Edo" featured in dozens of prints. Complete views of both banks of the Sumida River were also meticulously depicted as panoramic illustrations and published in scroll or book form. One of these books, illustrated by Hokusai, has survived to our days, and it is considered amongst the finest examples of its genre. Thus, it is possible to have a fairly precise idea of how the bridge and its surroundings must have looked like in 1814. Ukiyo-e also show how the bridge became packed with people who enjoyed the firework displays during summertime, a tradition started in 1733 (apparently the first ever in Japan) and still alive in modern Tokyo today. Tragically, this long-standing custom spelled the fate for the wooden bridge: on August 10, 1897, the overweight of the crowd caused a partial structural collapse with dozens of victims, and an iron bridge was built in its place in 1904. The iron bridge survived the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, but it was eventually replaced by a concrete-made version in 1932, which is still standing today, as a typical example of how Tokyo has radically changed its look throughout the decades.

Today, the number of bridges on the Sumida River south of Senju Bridge amounts to nineteen.

(fp)

(6 - to be continued)

© 2017 fp

© 2014-2015 Hinako Sugiura•MS.HS / Sarusuberi Film Partners

![WORK LIST[DETAILS]](/contents/works/design/images/left_title.gif)

terms of use

terms of use