History Special 3: About O-Ei aka Katsushika Oi

I. FAMILY MYSTERY Daughter of ukiyo-e artist Katsushika Hokusai and his second wife Koto, O-Ei is one of the very few female artists of the Edo period. And as of today, she remains shrouded in mystery. There are only ten works that most scholars agree to have been created by O-Ei almost for certain. Very little is known about her life, except for a collection of fragmented and often contradictory information. Her paintings are not inscribed with a date, although two illustrated books bearing the year of publication have survived. Even her birthdate is debated: maverick researcher Kazuyoshi Hayashi suggested 1791, while most scholars today tend to consider 1800 or 1801 as most likely. Researcher Gozo Yasuda has theorized 1798. In the comic book Sarusuberi, however, Sugiura seems to embrace the 1791 theory, with O-Ei aged 23 in 1814.

II. LIKE FATHER Accounts of the time all agree upon the fact that O-Ei shared with her father not only a great artistic talent, but also stubbornness and total disinterest for housekeeping. The two spent all day drawing. They never cleaned or cooked. They would order food from outside stalls, eat while working, and leave everything on the floor, turning their living place into a garbage dump. O-Ei once married to a painter named Minamizawa Tomei (approximately in 1819 according to Yasuda), but the marriage did not last, and she eventually returned to her father's place. Apparently, the marriage wrecked because O-Ei used to laugh at her husband's inadequate artistic skills. O-Ei never remarried, and assisted her father Hokusai the remainder of her life.

III. WHAT'S IN A NAME? A number of paintings bearing the signature "Hokusai's Daughter, Tatsu-jo" (or Toki-jo: the reading is debated) have led experts to believe that O-Ei used such name in her youth, when her father was using the art name Tatsumasa (or Tokimasa: again, the reading is debated). However, some of the ten works currently ascribed to her are signed as Oi (or Oi Ei-jo). There are several theories as to the origin of this art name, that she used after her divorce. The most colourful version has it that O-Ei had the habit of attracting Hokusai's attention quite abruptly by shouting, "Oi, oi, Father!" where "oi" is a Japanese equivalent to "hey, hey!" Yasuda pointed out that "Oi" simply derived from her father and master's art name, as at the time Hokusai signed as Iitsu, and pupils customarily took one character from their master's art name. Yasuda also suggested that "Oi" could be translated as "faithful to I[itsu]," thus reflecting that unique father/master-daughter/pupil relationship. Considering how much a witty man Hokusai was, the truth might as well lie in between. Her given name was Ei, with an honorary 'O' tacked on in front as typical for women's names in the Edo period, hence O-Ei. Nevertheless, her father brutally used to call her "Jaws" because of her strong chin. One thing is certain: she never used the art name "Katsushika Oi", which was completely made up by modern scholars.

IV. FIRE AND SMOKE O-Ei had a strange fascination for fires, which frequently occurred in Edo, attracting many onlookers. Unlike her father, she enjoyed alcohol and smoking the pipe: once she even ruined a painting in progress by dropping ashes on it, and though this happening made her stop the habit for a while, she restarted some time later. O-Ei is said to have been the only person by her father's side when he died in 1849, at the age of 89 (or 90 according to the Japanese counting system). It is easy to imagine how the loss must have hugely affected her. Hokusai biographer Kyoshin Iijima reports she restlessly changed her dwelling. But even Iijima, who wrote almost everything we know about O-Ei in 1893, could but offer three very conflicting versions of her whereabouts thereafter. It is commonly believed she died around 1857, but like her birthdate, nothing is known for certain about her last days.

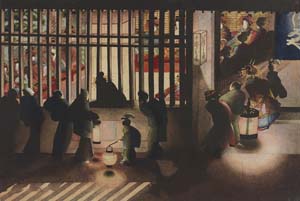

V. LIGHT AND SHADOWS Whatever birthdate is taken into account, O-Ei must have worked closely with her father for at least 25 years. Hokusai's late paintings, made when he was well into his eighties and had almost completely abandoned the woodblock print business, show outstanding vitality and innovation. From a letter written by Hokusai, it appears that publishers were fully aware that placing an order to "Hokusai" involved the option of having the job done by either father or daughter. Some even specifically asked for O-Ei's services. However, the final product was inevitably signed by the brand that sold better on the market: "Hokusai." This would explain the otherwise surprising scarcity of works bearing O-Ei's signature, but the contribution of O-Ei's talent to works bearing her father's signature is to remain in the realm of scholars' conjectures. Nevertheless, her artistic sensibility can be fully appreciated in her attention to both the concept and the execution of her works. A painting on silk entitled Courtesans Showing Themselves to the Strollers through the Grille (Ota Memorial Museum of Art), and depicting a night scene in the Yoshiwara pleasure district, is often considered as her masterwork, staging a sophisticated play of light and shadows which is totally unseen in any picture made in Japan at the time. Where Japanese ukiyo-e artists would simply represent night scenes as bright as day, O-Ei breaks up with any Japanese figurative tradition and boldly introduces chiaroscuro and perspective. Although impossible to prove, it is tempting to believe that O-Ei may have been exposed to European art, such as Flemish painters, as this painting seems to suggest. And accounts of a transaction for a series of paintings between Hokusai and the Dutch kapitan (chief factor) Johan Willem de Sturler in 1826 would make this hypothesis not at all unlikely. But undoubtedly, she experimented in territories his contemporaries wouldn't dare or care, with outstanding results. A free-spirited woman ahead of her times, O-Ei was to fascinate those willing to discover her.

(fp)

(3 - to be continued)

© Production I.G

![WORK LIST[DETAILS]](/contents/works/design/images/left_title.gif)

terms of use

terms of use