Interview with Mamoru Oshii (1)

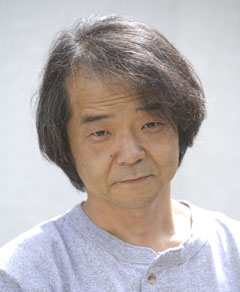

| Mamoru Oshii Born in Tokyo on August 8, 1951, Mamoru Oshii is one of the most remarkable personalities in modern Japanese filmmaking. He introduced introspective philosophical speculation into the world of animation, influencing at the same time movie creators all around the globe with his visionary style. Oshii joined the animation industry in 1977. His main works are Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer (1984) the epoch-making Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Innocence (2004, nominated for the Palme d'Or at the Festival de Cannes). Oshii has also directed a number of live-action features, including Avalon (2001). The Sky Crawlers, was nominated for the Golden Lion at the 65th Venice Film Festival, selected in the 33rd Toronto International Film Festival and was greeted with three awards at Sitges 2008. |

PART 1

The Sky Crawlers describes an alternate reality in which war has turned into a sort of entertainment. Are you saying that our world is getting to that point?

I'm pretty sure we are heading that direction and we are also quite close to the goal. In the movie, war is not fought between nations, but private war subcontractors. As far as I know, 20% of the units deployed in Iraq are managed by private companies. I'm sure this percentage is going to increase as the so-called most developed countries are gradually abandoning the conscription system and conduct their conflict subcontracting to private companies. This is currently related to mere economic factors, but the step from here to staging a war as entertainment might be dramatically short.

This said, the First Gulf War clearly demonstrated that we watch real wars on TV as they were shows. The First Gulf War was a conflict broadcast worldwide in real time, with CNN journalists telling their live commentary as in a soccer world cup. The day technology and satellites made live broadcast reach every corner of the planet at the same time, even war could turn -or be turned- into a global show. We should then ask ourselves why we are so fascinated by watching wars far away from us, or watching very violent movies, or why do we cheer at our country's national team crushing opponents from other nations in any sport competition.

In The Sky Crawlers, the actors on the stage of this war as entertainment are teenagers who don't become adults. Do you believe that real communication between youngsters and adults is impossible?

The concept of children as persons is not so old and obvious. There was a time when a rite of passage, or initiation, existed in the Japanese society. This rite marked a child's step into adulthood. As for Europe, it is my understanding that until very recent times -recent in terms of human history, I mean- children were not even considered as "persons," but a property of adult people. On the opposite side, there are countries where 10-year-old kids are enrolled as soldiers. Therefore, before theorizing about possible communication between children and adults, we should first establish how, within a social system, adults consider what is "not adult," or child.

Man and Machine. Do you think that a peaceful coexistence is possible?

Are we talking about man-machine interface, then?

Since the early Seventies, animated TV shows in Japan featured stories where human beings are deeply connected with the machines they pilot, being these spaceships or giant robots. Machines were seen as an extension of the human body, and the human body was part of the machine.

There is a quite simple reason for this, namely the necessity to establish immediate identification between the robot and the character that controls it. We may also add a cultural factor, as we Japanese have no particular resistance in projecting our own emotions towards objects, being animism a deeply rooted element in our culture. Any object can be kami, or god.

Apart from this, we can observe how the strong interaction between man and machine started from a mere narrative need, and evolved into what we can see now. It is interesting to notice how reality followed animated fiction through the same path.

If you allow me the comparison, the network described in Ghost in the Shell is now widely spread in our everyday life in the shape of the most advanced mobile terminals, that calling "cellular phones" would be far too reductive. Of course, the terminal is in our hand and not implanted in our brain, but I think the basic concept is pretty much the same.

In this movie, the man-machine relationship is not necessarily the story's main theme, yet there's a reason I decided to use airplanes with reciprocating engines and propellers instead of jet engines. When flying this kind of planes, the pilot is required to use his physical strength in order to fully control the machine, as the plane can be maneuvered only if a human pilot pulls tension cables with much effort.

I wanted to depict as vividly as possible the psychological and physical pressure the pilots have to endure during an air battle. At the same time, the audience of this war as a show can only see two flying chunks of metal confronting without even touching each other. It's an enthralling, aseptic slaughtering without consciousness that in the end people die in there.

Air warfare removes the psychological weight generated by direct witnessing of a person killing another. It's a murder that distance and speed deprive of its harshness.

(1 - to be continued)

Part of this interview was originally published on the Italian newspaper La Rebubblica on August 27, 2008. Interview by Luca Raffaelli.

![WORK LIST[DETAILS]](/contents/works/design/images/left_title.gif)

terms of use

terms of use